|

|

|

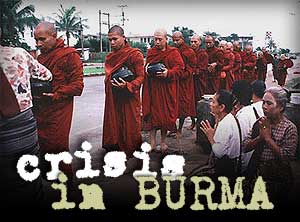

Home Asia Pacific South East Asia Myanmar Myanmar Protest News Myanmar Monks Lead Anti-Junta ProtestsBy MICHAEL CASEY, AP, Sept 16, 2007BANGKOK, Thailand -- Monks have vandalized shops of those supporting the dictatorship in Myanmar, briefly taken local officials hostage and are now threatening to launch a boycott as early as Tuesday against the military leaders and their families.

"Monks are our only hope now as they always have been in Myanmar political history," said Hla Myint, a 75-year-old schoolteacher. "The military rulers can easily crush protests by students and other people. But brutal suppression of monks usually results in negative consequences and further protests."

Without an apology, monks across the country have threatened to march Tuesday from their monasteries, cut off communication with the military and their families and refuse alms — a humiliating gesture that will likely embarrass the junta. "What the (junta) did in Pakokku is unforgivable. The monks are frustrated and angry," said Zin Linn, information minister for the Washington-based National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma, which is Burma's government-in-exile. "This boycott is significant because other underground labor unions, underground student unions and activists are calling on one another to join the boycott," he said. "I expect the demonstrations will grow bigger than ever. People may join with the monks and we may see chaos and disorder." A chief abbot at a Yangon monastery said the boycott will have a symbolic importance in the ongoing struggle against the junta. "In a staunchly Buddhist country, such a boycott is the most severe form of punishment for a Buddhist," said the abbot, who refused to be identified for fear of reprisals. "The boycott brings extreme shame to the ruling junta and should be taken seriously." Monks in Myanmar, also known as Burma, have historically been at the forefront of protests — first against British colonialism and later military dictatorship. They also played a prominent part in the failed 1988 pro-democracy rebellion that sought an end to military rule, imposed since 1962. The uprising was brutally crushed by the military and thousand were killed. This time around, the military regime has appeared nervous and indecisive in its dealings with the monks. Since protests broke out Aug. 19 after the government hiked fuel prices by as much as 500 percent, it detained dozens of pro-democracy activists and cut off the phone lines as the country's main opposition group the National League for Democracy or NLD. But it has yet to arrest any monks, preferring a mix of heavy-handed threats, gentle persuasion and outright pleas to convince the estimated half-million Buddhist clergy to stay off the streets. It stepped up surveillance around monasteries in major cities to keep young monks in check and order monks to remain in some monasteries. It has accused them in newspaper articles of being tools of the NLD and other government critics who want to overthrow the government. "Exploiting these situations, some are trying to disrupt the prevailing peace, stability and law and order and the momentum of development and to derail the seven-step road map," the government said, blaming everyone from foreign governments to troublesome monks for fueling the protests. But last week in an evident attempt to improve its image, high-ranking officials have been making high-profile donations of cooking oil and other donations to Buddhist monasteries, according to the state-controlled press. Making donations to temples is a traditional way of showing respect. Experts appear divided over whether the monks can persuade the public to join the protests — partly because civil servants have been removed to the new capital in the remote town of Naypyitaw, while universities have been moved out of Yangon and other big cities to sideline students. Some experts said monks could persuade rural residents to get involved because they hold such sway in the countryside as well as elements of the military who feel they would be unfairly slandered by the boycott. "This could also create divisions in the military," said Soe Aung, spokesman for the pro-democracy group National Council of the Union of Burma which is based in Thailand. "The majority of the military is already suffering from the mismanagement of the economy." But other experts argued that fear will likely trump the boldest of actions by the monks, with many citizens afraid to challenge a military with a history of brutality. "The military is much stronger than they have ever been in Burmese history," said David Steinberg, a Myanmar expert at Georgetown University in Washington. |

Get your Korean Buddhist News here, brought to you by BTN-Buddhist Channel |

|

The Mandala app brings together Buddhist wisdom and meditation techniques with the latest insights of psychology and neuroscience to handle the challenges and complexities of modern life. The App offers a series of engaging talks and conversations with experts on a wide variety of topics, such as managing stress, dealing with adversity, developing greater resilience, cultivating empathy and compassion, creating healthy relationships, and many more. These topics are explored to help find greater peace, meaning and joy in our lives. Our panel of experts include Dr, Thupten Jinpa, Daniel Goleman, Kelly McGonigal and others.FREE DOWNLOAD here |

| Point

your feed reader to this location |

| Submit an Article |

| Write to the Editor |

Nearly a month into the worst demonstrations to hit Myanmar in decades, the saffron-robed Buddhist clergy are emerging as the focal point of the anti-government protests. With dozens of pro-democracy activists behind bars or in hiding, most people are counting on monks — who have a role in almost all aspects of society from weddings to funerals — to take the lead in challenging the repressive regime in the mostly Buddhist country.

Nearly a month into the worst demonstrations to hit Myanmar in decades, the saffron-robed Buddhist clergy are emerging as the focal point of the anti-government protests. With dozens of pro-democracy activists behind bars or in hiding, most people are counting on monks — who have a role in almost all aspects of society from weddings to funerals — to take the lead in challenging the repressive regime in the mostly Buddhist country.