|

|

|

Home Asia Pacific North Asia S/N Korea Temple Stay Modern Day Temple StayBy Kate Liptrot, The Korea Times, March 15, 2006

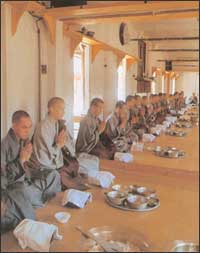

In all of Korea, nothing more readily symbolizes ancient tradition than the Buddhist temple. Seoul, South Korea -- In a landscape dominated by concrete apartment buildings, the carved and colourful wooden temples stand apart, the life within seemingly untouched by development as though modernity and progress have together been left outside like a worshipper’s pair of shoes.

Suspecting the promoters of a fondness for hyperbole, but nevertheless believing temples to be havens from the outside world, my friend and I set off on what we hoped would be an enlightening, weekend retreat. On arriving, we discovered that a huge cement mixer had intruded upon the calm which we could only presume had previously suffused the building and its grounds. However, not wanting to let this colour our judgement, we sat calmly drinking tea and awaiting the arrival of our English-speaking mentor, Patrick. He soon appeared, shaking his shaggy hair out of a motorcycle helmet, leaving a gleaming red Harley to cool in the shade of a tree. Bald and be-robed Patrick was not, for he was no monk but a casual practitioner of Buddhism. There were six of us on the program, and Patrick made the most of our manpower by engaging us in the ritual of solemnly banging a huge drum, a signal to all that worship was about to begin. We took turns until we had beaten the instrument fifty, sixty times, and then we silently made our way in to the great hall. Unfortunately, the ceremony was cancelled because the chief monk had a cold. With the noise of the drum still echoing in our ears we decided that, rather than let our efforts be thwarted by one man’s runny nose, we would spend half an hour meditating. Patrick had advised us to `watch’ either our thoughts or our breath, both of which are methods that supposedly focus the mind on the present. I opted for the latter because all it demanded was that I count each time I exhaled, which seemed straightforward enough. However, my fidgety brain proved to be easily distracted. I had spotted a Walmart superstore near the temple which would not have afforded a second thought had I been back home, but I had spent enough time in Korea to feel a little starved of Western goods, and so I indulged in a consumerist fantasy that gave me such interest and pleasure I forgot all about watching my breath. Meanwhile, three giant bronze Buddha statues which proved to be less distractible than myself, maintained their watch over proceedings the entire time, so that I later imagined their eyes disapprovingly fixed upon me. The meditation session ended and we left the ceremonial hall only to return later that evening. We again make ourselves comfortable on the prayer mats, although on this occasion we were settling down to watch not our breath or our thoughts, but Brad Pitt. Along with the traditional incense, flowers, and candles, the ceremonial hall was also home to the temple’s TV, and as Patrick had no other ideas we chose to watch `Seven Years in Tibet,’ with the gaze of Buddha upon us once more. It may have been a little indulgent of us to spend our evening in this way, but our activities the following day more than compensated for this temporary slip. After rising at five in the morning for meditation and breakfast we then sat through a one-and-a-half hour service delivered entirely in Korean by an eminent Buddhist with tell-tale traces of donut sugar in his beard. We understood not one word. The previous day, Patrick had defined the shifting of emotions as ``internal weather,’’ and if anyone had taken a forecast they would have discovered that my boredom and frustration were the source of a miserable, grey downpour. Feeling more alienated than involved as a result of the service, we sat down to our final meal before departing. The temple’s sole nun presided over proceedings, radiating an inner calm, which was one of the few things that corresponded with my expectations. It may seem odd that I found the most normal feature of the temple to be a woman whose lifestyle, character, and beliefs were utterly at odds with my own, but then this was a place that had confounded my expectations, where Brad Pitt and Buddha were side by side, where monks indulged in sugary American snacks, and where Patrick felt comfortable playing his electric guitar in the prayer room. Twenty-four hours had after all been sufficient time for me to begin to see differently, although not in the way that the Temple Stay slogan intended, for it was not the cultural differences that had taken me by surprise, but the similarities. ``Changing the Way You See the World’’ suggests that the values of the east and the west are mutually exclusive, and that a person must choose between these two different perspectives of the world. However, Patrick and the Korean Buddhists brought in to co-existence two cultures which were neither fully integrated with one another nor entirely separate. It is this mix of traditional culture with the American influences of capitalism and consumerism that accurately reflects the nature of modern day Korea. ------------------------------------------------------- |

|

|

| Korean Buddhist News from BTN (Korean Language) |

|

|

|

|

Please help keep the Buddhist Channel going |

|

| Point

your feed reader to this location |

|

This perception is encouraged by the slogan of the Temple Stay Korea program, which claims that a twenty-four hour sample of the monastic lifestyle is enough to ``change the way you see the world.’’

This perception is encouraged by the slogan of the Temple Stay Korea program, which claims that a twenty-four hour sample of the monastic lifestyle is enough to ``change the way you see the world.’’