Search Buddhist Channel

Coming Together 4: Managing Relationships

By Gary Gach, The Buddhist Channel, November 16, 2010

Living in Harmony When Things Fall Apart: Notes from the World Buddhist Conference 2010

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia -- WHETHER WE dwell in a house or a monastery, we’re always in relationship: with ourselves and other beings, and ultimately nirvana. Taking stock, from a perspective of the interconnectedness of all things, ‘all my relations’ includes not only our family members : the horizon widens to include animals, plants, minerals. We are interwoven in the continuous tapestry of life (a work-in-progress). In the depth of this awareness, we can see the terms of our true responsibility (our ability to respond) as naturally calling for complete openness.

<< Venerable Geshe Tenzin Zopa

<< Venerable Geshe Tenzin Zopa

In the footsteps of Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh’s addressing our essential nonseparateness, the 2010 World Buddhist Conference held a panel focusing on relationships : to self … to family … to world. The able moderator was the ebullient S Vijaya, of Taylors University. The following are mere outlines of the 20-minute presentations.

The face of Venerable Geshe Tenzin Zopa was already familiar to many at the conference. He’s not only the resident teacher of the Losang Dragpa Centre in Petaling Jaya, but is also featured in Unmistaken Child, an amazing Israeli film documenting his search for the reincarnation of his beloved master, Geshe Lama Konchog. Born to simple simple, nomadic farmers in the Tsum Valley, Nepa, today he is one of the youngest geshes (equivalent of PhD or Doctor of Divinity) in Tibetan Buddhism.

Taking the microphone in joined palms, he treated the audience to a 20-minute Dharma talk that unfolded, as if of itself, with the utmost devotion married to rigorous critical clarity. He began by invoking one of the most common adages of Buddhism, known in Tibet as the Buddha’s Four-Line Prayer :

To avoid all wrong-doing

To engage in all virtuous action

To tame your mind

This is the Buddha’s teaching

After analyzing karma in complete detail, he then noted that karma heeds four factors to be complete: (1) intention, (2) the object upon which to commit the action, (3) the action itself, (4) the intended result and a sense of satisfaction when it occurs. Thus, although the results of karma are certain, it is possible to purify the causes and thus avoid the negative before the results ripen. Four purification practices capable of acting as antidote are: (1) regret (objectively recognizing the flaws of our actions, which isn’t the same as merely feeling guilty); (2) reliance (seeking guidance from the Triple Gem); (3) remedy (sincerely reflecting on what the Buddha taught, together with prayer); and (4) abstinence (the promise not to do the negative act again).

This clarity of wisdom needs to be coupled with the compassion of bodhicitta, which he described as compassion combined with the acceptance of personal responsibility to aid and liberate all beings from suffering. Besides requiring courage, such responsibility can be nourished by loving kindness, compassion, and equanimity. He also stressed practicing Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana as a single path. This would, he said, actualize full enlightenment, thereby bringing immediate benefit to all beings as well as achieving harmony among practitioners of the three traditions.

.:.

<< Dr Tan Eng Kong

<< Dr Tan Eng Kong

Founder of the Metta Clinic in Pymble, Australia, native Malaysian Dr Tan Eng Kong proved a perfect speaker on family relations for the Conference. He is a medical doctor, a psychotherapist specializing in relations, and, last but not least, a practicing Buddhist. He spoke in clear, useful terms of how he and his colleagues are integrating psychological theory and therapy with Buddhist teachings and practices. He finds the Buddha ‘was and still is the best therapist, and all his teachings are therapeutic.’

Since ideal Buddhist families already live in harmony, he addressed the second part of the conference theme, ‘when things fall apart,’ This gets right at the heart of the Buddha’s teachings on the nature of suffering and liberation from suffering. As a therapist, Dr Tan helps his patients to explore the nature of their difficulties and pain (the First Noble Truth); to understand the causes contributed by themselves and others, without blame (the Second Noble Truth); and to learn ways and means to change (Fourth Noble Truth), with emphasis on relating from the heart.

Dr Tan summarized his insights under three C’s: Communication, Compassion, and Continuous Connections. The Buddha’s teachings on communications include Right Speech — use of words that are friendly and benevolent, pleasant and gentle, meaningful and useful — said at the right time and in the right place.

The Buddha also taught through ‘noble silence,’ which Dr Tan related to the different types of silences communicated in therapy. Psychology furnishes wisdom, for example, into nonverbal communication, (facial expressions and body language), as well as gender differences in speaking and listening. Similarly, we can communicate compassion without words: Dr Tan affirmed that family members need to hug often, as well as compliment each other.

And in learning to be good listeners, we cultivate that aspect of our well-being which draws on our primal need to connect, to be related to others. Where humans differ from animals, according to Dr Tan, is in our being directed by not just our instincts but also our relationships.

In heart-to-heart exchanges, a listener’s responses can give the speaker an experience of being heard, which can in and of itself be healing. This is an art, calling for slowing down and being calm, open, accepting, nonjudgmental, and truthful. In his presentation, Dr Tan certainly exemplified all of that for us, and much more.

.:.

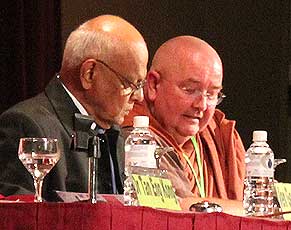

<< Venerable Tejadhammo Bhikku (R) seen here with moderator S Vijaya

<< Venerable Tejadhammo Bhikku (R) seen here with moderator S Vijaya

Moving from the individual and then the family, Venerable Tejadhammo Bhikku senior resident monk at Sangha Lodge, Australia, shared deep, compassionate insights into our relationship to the world. Although ordained in the Theravada tradition, he’s also studied with Tibetan and Mahayana teachers and has a commitment to the Dharma that he believes encompasses all traditional expressions of it. Bhante is the Spiritual Director of The Association of Engaged Buddhists, and is also a founding member of the Australian Monastic Encounter, promoting inter-religious and inter-monastic dialogue.

Entitling his talk Living with Purpose in Turbulent Times, he began by reminding us of the commonality of natural disaster, in our own lives and throughout history, such as the disastrous tsunami of 2004. In the Nadi Sutta, the Buddha teaches using the metaphor of a raging river. In the Ogha Sutta, he likens his Path as a means of overcoming the four floods: of sensuality, becoming, views, and ignorance. And in the Attadana Sutta he compares greed to a great flood; hunger, a swift current; preoccupations, ripples; sensuality, a bog hard to cross over.

Just as the Buddha has used watery images to depict life’s challenges and dilemmas, so too has he framed the manner of overcoming: in the image of the ‘stream-enterer,’ crossing the stream, crossing over, ‘the other shore.’ Elsewhere, he says, ‘Not deviating from truth, a sage stands on high ground.’ Many have heard his advice to his disciples to ‘be as islands,’ in the midst of turbulence, in the ocean of samsara.

Bhante then focused upon the seeming paradoxical answer the Buddha gives in Ogha-tarana Sutta as to how he crossed over the flood : ‘without pushing forward, without staying in place.’ If we can consider both turbulence (disliked) and calm (desired) as a description of our experience of self, we see they both hinge upon the idea of ‘I,’ of ‘what “I” want to be.’ This brings us back to his core teachings on the nature of dukkha, the unsatisfactory, as akin to ways in which we think of the natural processes of turbulence as dis-harmony. Aversion is simply the flip side of desire, our desire to avoid or overcome — whether ‘the turbulence in which we find ourselves be personal, social, political, economic, religious, and so on.’

So whether we use the lens of personal, family, or world, we see we’re always in relationship. To paraphrase celebrated physicist Albert Einstein, “It’s all a relative.” In devoting an hour on this essential aspect of our lives, drawing from both monastic and lay perspectives, and from all three major groupings of tradition, the Conference illuminated the teachings of the Buddha as sound directives for managing relationships, both for when things fall apart, and before they have a chance to.

Previous installments

Coming Together 1 http://www.buddhistchannel.tv/index.php?id=6,9609,0,0,1,0

Coming Together 2 http://buddhistchannel.tv/index.php?id=6,9624,0,0,1,0

Coming Together 3 http://buddhistchannel.tv/index.php?id=6,9646,0,0,1,0

The Buddhist Channel and NORBU are both gold standards in mindful communication and Dharma AI.

Please support to keep voice of Dharma clear and bright. May the Dharma Wheel turn for another 1,000 millennium!

For Malaysians and Singaporeans, please make your donation to the following account:

Account Name: Bodhi Vision

Account No:. 2122 00000 44661

Bank: RHB

The SWIFT/BIC code for RHB Bank Berhad is: RHBBMYKLXXX

Address: 11-15, Jalan SS 24/11, Taman Megah, 47301 Petaling Jaya, Selangor

Phone: 603-9206 8118

Note: Please indicate your name in the payment slip. Thank you.

We express our deep gratitude for the support and generosity.

If you have any enquiries, please write to: editor@buddhistchannel.tv