Malaysian in Singapore death row becomes devout Buddhist

By RASHVINJEET S.BEDI, The Star, January 23, 2011

Singapore -- Two years have passed since Malaysian Yong Vui Kong was sentenced to death by a Singapore court for a drug offence. As campaigns to save him continue relentlessly, he has turned to Buddhism, meditates and counsels other inmates and prison wardens.

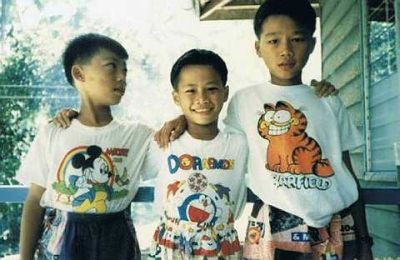

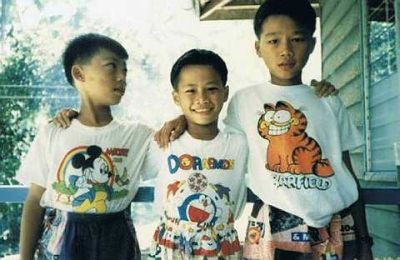

<< Those were the days: Vui Kong with his brothers

<< Those were the days: Vui Kong with his brothers

Every day counts for Yong Vui Kong. Last Tuesday, he celebrated his 23rd birthday in prison in Singapore, a milestone for someone who has been facing the hangman’s noose over the last two years.

Vui Kong was sentenced to the gallows on Jan 7, 2009 for possession of 47.27g of heroin. Initially, he was to be executed on Dec 4 the same year. He petitioned for a judicial review of the rules that can potentially allow offenders like him to be spared the gallows, but it was turned down last year. He subsequently appealed the decision, and last Monday the republic’s Court of Appeal reserved its judgment.

Countless blogs have been set up in support of Vui Kong, and more than 22,300 people have signed in to the “Save Yong Vui Kong” Facebook group page.

Amnesty International Malaysia staged a play based on his life while International news station Al-Jazeera made a documentary about the visit of campaigners to Sandakan, his hometown.

In Singapore, a group of supporters commemorated his birthday with a song and a cake. For every day he is alive, it means hope for the clemency campaigners whose efforts have continued unabated.

So why did 109,346 people sign a petition (collected on the streets and not the Internet) asking the Singapore President for clemency? Why are people concerned about a young man they don’t even know, one whom detractors say is a criminal and should have known better than to smuggle drugs?

The Save Vui Kong Campaign coordinator Ngeow Chow Ying believes that Vui Kong’s plight has touched hearts because of his circumstances.

“I think it’s his background and the fact that he has repented. I know people who support the death penalty for drug crimes but are sympathetic towards Vui Kong,” she says.

Ngeow acknowledges that the group is sometimes misunderstood.

“We are not asking him to be let free. He has to take legal responsibility for what he did. We are asking for clemency,” she stresses.

Kirsten Hans of the We Believe In Second Chances in Singapore says she and her fellow campaigners have been accused of neglecting the victims of drug abuse and their families.

“I’ve been called a criminal-hugger,” she says.

For the record, Vui Kong was caught with heroin in June 2007, a crime that warrants a mandatory death sentence. He was barely 18 at the time. Because of his age, trial judge Justice Choo Han Teck asked the prosecution to consider reducing the charge against him.

The prosecution declined, and Vui Kong was given the mandatory death sentence.

A victim of circumstances

Vui Kong is the sixth in a family of seven siblings. His parents were divorced when he was only three and as a result, his mother Liaw Yueng Kuan was forced to raise the family single-handedly. She earned a paltry RM220 monthly washing dishes at a hawker stall.

Because of the dire situation, only Vui Kong and his two elder brothers lived with their mother and reportedly abusive grandfather. The other siblings lived with relatives.

Of all the siblings, only Vui Kong’s younger sister Yong Vui Fung, now 21, completed studies until secondary five.

His elder brother Yun Leong, 26, a kitchen helper in Singapore, who visits Vui Kong every Monday in prison, says growing up was very tough because of the negative atmosphere.

According to him, his mother was always abused and beaten by their grandfather. The brothers, meanwhile, were forced to take care of their grandfather’s patch of oil palm, a laborious task.

Vui Kong dropped out of school when he was 11 and started working odd jobs, including washing cars for RM3 a day.

At one point, he stayed with a friend because his workplace was far from his home.

Because of his meagre salary, he decided to try his luck in Kuala Lumpur when he was 16, getting a job as a kitchen helper.

Vui Kong got into the “wrong company” and started selling pirated DVDs in Petaling Street, earning about RM1,000 monthly, says Yun Leong.

There he met a “big brother” who bought him meals in hotels and expensive clothes. Vui Kong then started debt collecting before delivering “special packages”.

He did not know much about the law and the boss lied to him, telling him that peddling DVDs would earn him seven years in jail while peddling drugs would only get him two years in prison, at the most, says Yun Leong. “He was a naive kid.”

At that time, their mother was suffering from depression and Vui Kong was desperately looking for money to help her.

<< The picture of the Bodhi sattva of the netherworld that Vui Kong drew for his lawyer M. Ravi. The drawing was done with a four-coloured ballpoint pen and took more than 30 days to complete.

<< The picture of the Bodhi sattva of the netherworld that Vui Kong drew for his lawyer M. Ravi. The drawing was done with a four-coloured ballpoint pen and took more than 30 days to complete.

Three days before getting caught, Vui Kong flew to Sandakan to celebrate his mother’s birthday.

In fact, his last wish before his slated execution in 2009 was to see his mother.

Until today, his mother does not know that Vui Kong is facing the death sentence. “He told her that he was going for a pilgrimage far away,” says Yun Leong.

Onto the path of Buddha

It is learnt that Vui Kong has undergone a complete transformation since entering jail.

He has taken up Buddhism and spends a lot of time on prayer and meditation, waking up by 4am every day. He has also become a vegetarian and taken a new name, Nan Di Li, from the Buddhist Dharma.

“He is glad that he was caught because if not, he might still be doing bad things,” says Yun Leong.

Vui Fung says she could not believe the change she saw in her brother when she met him in prison.

“He always had a good heart, although not necessarily good habits. I remember him always waking up late in the day,” she recalls.

Vui Kong’s lawyer M. Ravi, who has been working pro bono, says that when he first met Vui Kong, the latter could hardly speak a word of English and only spoke broken Malay and Hokkien. Now, 80% of their conversation is in English.

“Every time there is a legal submission, he would bring his dictionary along and scrutinise the submission. He would always ask why one word was used and not another,” says Ravi.

He says Vui Kong’s mother was impressed with her son when she saw him in December 2009.

“She was crying when she heard his Mandarin,” says Ravi.

Similarly, Ngeow, who has been reading letters to his family, says that he started writing simple letters asking them how they were. But as time passed, the letters became more philosophical, with quotes from Buddhist teachings.

“His grammar has improved tremendously as well,” she says, adding that 30 of these letters have been compiled into an e-book.

Vui Kong’s compassion grew as well. He would save the biscuits he got in the morning and on the way to the library, he would distribute them to the other prisoners, says Ravi.

“He also counsels the other inmates and even prison wardens,” he adds.

“Not a single prison warden can accept his execution. A prison guard told me that he is the gentlest soul he has ever met and they all have benefited from him.”

Ravi considers Vui Kong to be an enlightened soul and is learning meditation from him.

“I feel recharged after seeing him,” Ravi says.

Vui Kong also drew him a picture of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, often referred to as the Bodhisattva of the netherworld because of his vow not to achieve Buddhahood until “all the Hells are empty”.

The drawing with a four-coloured ballpoint pen took more than a month to complete.

“He would kneel down, meditate and draw the picture,” says Ravi, adding that Vui Kong is talented in art.

Vui Kong is also thankful to all those who have been supporting his clemency appeal.

“I showed him a picture of Singaporean activists who rallied in the park in support of his cause. He took at least 30 minutes to look at the picture to know all the faces,” Ravi says.

Vui Kong also wrote thank you letters to each person in the picture, including a five-year-old girl, he adds.

Yun Leong says his brother will accept whatever happens and is not afraid of the noose.

“Vui Kong has accepted his fate because everyone will die anyway. He took the wrong path and is not afraid to accept the consequence of his actions. He just wants his life to have meaning,” he says.

Yun Leong adds that his brother wants to join the anti-drug campaign and guide other youngsters towards the right path.

“He tells people not to take the easy way out and not to trust anyone blindly,” he says.

Ngeow believes Vui Kong would make a good advocate for an anti-drug campaign.

“His story can inspire others not to make the same mistakes, and those in similar circumstances. If Vui Kong speaks to them, they would probably listen to him,” she says.

<< Those were the days: Vui Kong with his brothers

<< Those were the days: Vui Kong with his brothers << The picture of the Bodhi sattva of the netherworld that Vui Kong drew for his lawyer M. Ravi. The drawing was done with a four-coloured ballpoint pen and took more than 30 days to complete.

<< The picture of the Bodhi sattva of the netherworld that Vui Kong drew for his lawyer M. Ravi. The drawing was done with a four-coloured ballpoint pen and took more than 30 days to complete.